- Home

- Gary Alexander

Dragon Lady Page 2

Dragon Lady Read online

Page 2

In 1965, Vietnamese would still stare at us and our round eyes. Ziggy was a sci-fi lover, with a fanatical preoccupation with the planet Mars. We could’ve been Ziggy’s Martians, we were such novelties.

While the adviser bullshit was coming to an end and we were taking over the fighting, if your number was up, you were as apt to have a barstool blasted out from under you as catching a North Vietnamese bullet between the peepers.

We were unable to stuff the box into the little cream-and-blue Renault taxi as is. To make the air conditioner fit, Ziggy ripped the cardboard off like he was peeling an orange. Half the people on the street did the airman’s see-no-evil. The other half gawked, not sure what they were seeing.

That’s what this war did for you.

Gave you fresh experiences every single day.

3.

AFTER ZIGGY and I installed the air conditioner in the window behind Captain Dean Papersmith’s desk and cranked it up full blast, the captain closed his eyes and smiled blissfully. He fluttered his pockets and flapped his shirt against his bony chest. He cooed like a pigeon. Until now, the only man in the outfit with an air conditioner was our commanding officer, Brigadier General Whipple, and his machine was unreliable.

“Private Joe, Private Zbitgysz, I may have misjudged you. Good work, men. A number one, can-do job,” Captain Papersmith said. “I know resourcefulness and possibly heroism was involved, given the nature of this hellhole city. By the way, did you hear? The VC blew up the U.S. Embassy. A terrible shock. It caught everyone by surprise.”

Ziggy and I let our jaws appropriately drop. As I did so, I was distracted as always by the photographs on the captain’s desk. The one in the large gilded frame was a professional color portrait of him and his horse-faced wife and their two children, a sullen boy, who had juvenile delinquent written all over him, and a grinning girl, who already knew the score. His missus wore a pearl necklace and a bouffant as tall as Marge Simpson’s would be.

Mrs. Dean (Mildred) Papersmith was an heiress in a clan that manufactured drawing instruments and technical products. Their cash cow was the slide rule, in which they ranked second to the venerable Keuffel & Esser. I’d owned one of Mildred’s family’s slide rules. For my one disastrous quarter as an engineering major, I’d had to purchase one.

Little did Captain Papersmith or anybody else in 1965 know that in a decade the pocket calculator would relegate the slide rule to a Smithsonian relic. It would obliterate his better half’s family firm and trust fund, a circumstance that would cause the good captain to suffer yet another nervous breakdown.

***

Please allow me to pause here for a moment. I apologize for the boldface type and the italics. It won’t happen again. I have to explain a few things before we proceed. It’s extremely important that I do (at least to me) and that I have your full attention.

I am not clairvoyant, I am not Nostradamus. I am not predicting the future from 1965. I am in the future, in The Great Beyond, or rather, from your point of view, in the present, speaking at the very instant you are reading this, whenever that might be.

The loose definition of “the great beyond” is the afterlife, life after death, and so forth. Which is precisely what The Great Beyond is.

Is it Heaven or is it Hell? Beats the hell out of me. Thanks to the psychological games They play with me, one day it’s one, the next day the other.

I do know that The Great Beyond is a municipality. Whether it’s a town, city, county, state, nation, continent, world, solar system, universe or galaxy, I do not know. The people (?) who run this place are probably capable of building a chain-link fence around infinity, so their accomplishments and capabilities are limited only by my imagination.

I’ve already mentioned the non-stop elevator music (“Lady of Spain” now playing) and the San Diego climate, but I’ve broken the narrative flow of this yarn long enough. The travelogue will continue later.

***

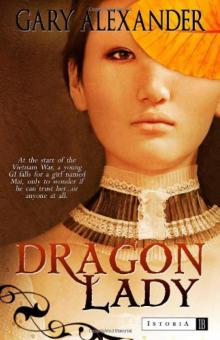

Tucked into the picture frame of the all-American household was a Polaroid snapshot of the captain’s girlfriend and the woman of my dreams. My Dragon Lady had been inserted as if she were the captain’s car or favorite pooch.

Thus far, sadly, the Polaroid was the extent of my relationship with her. I alone knew her as the Dragon Lady. Beginning then with her inaccessibility, she’d break my heart again and again, till it was a heap of shattered china.

My Dragon Lady didn’t wear the red metallic gowns with high collars as did her comic-page namesake in Terry and the Pirates (like the panel I kept in my wallet, nestled next to a rubber and, figuratively, my heart), but rather the traditional Vietnamese áo dài, a long silken tunic split at the sides, worn over loose pants.

Unaccompanied by her cartoon counterpart’s long ivory cigarette holder, she projected an innocence that I didn’t swallow for a moment. She was lovelier than the infamous Madame Nhu, sister-in-law of South Vietnam’s late president. My Dragon Lady made the Mona Lisa look like a hound dog. Her cheekbones were higher than the Chrysler Building stacked atop the Empire State Building. She seemed to be gazing beyond the photographer, presumably Captain Papersmith, straight into my eyes.

She was satiny soft and as tough as a hardware store full of nails, a contradiction that simultaneously gave me goose bumps and a hard-on. I’d looked and looked for an ideal complement to her visage, a tinge of cruelty in her eyes or at the corners of her mouth, and had found none. But nobody was perfect.

To be so obsessed by a combination of a Sunday comic and a low-resolution photograph was by any definition a psychological illness. I accepted my malady then and I relish it from my present aerie. If I were a sick puppy, so be it. The last thing in the world I wanted was the services of a competent shrink. To be cured would be unbearable.

As I continued staring, Captain Papersmith snapped his fingers. “Yoo-hoo, Private Joe. Are you with us?”

“Yes sir.”

He glanced at his watch. “Where have you men been today?”

We shrugged in unison.

“The air conditioner requisition does forgive you for being unaccounted for much of the day. However, I have an important mission for you. It has to be accomplished ASAP.”

Where we’d been was avoiding our duties and settling a bet. I’d told Ziggy about a book I was reading on U.S. presidents, on how George Washington had not pitched a silver dollar across the Potomac River, but supposedly a stone or a penny across the smaller Rappahannock.

“It’s lore,” I’d told Ziggy. “In the category of chopped-down cherry trees and wooden teeth.”

“Fucka buncha lore,” he’d rebutted. “Anyone can toss a dollar across a river.”

I’d said, “Oh yeah?”

He’d said, “Yeah, we got this river here that’s a pissy-ass little river.”

“Like Cuba’s a pissy-ass little island? Ask the Bay of Pigs survivors.”

“Who said shit ’bout some island?”

Well, off we’d gone. In this day and age, we could plead Attention Deficit Disorder for this sort of meandering stunt. Back then it was 24-karat goldbricking.

We’d ridden a taxi through downtown Saigon to the skinniest part of the Saigon River, which was still awfully wide. Ziggy wouldn’t’ve thrown a silver dollar even if we’d had one. We weren’t that flaky. He did fling a flat rock that skipped a third of the way out. Not a bad effort, but I won the wager. We were headed back to the outfit by way of a couple of bars when we’d come upon the air conditioner.

“We were out being heroically resourceful for you, sir,” I said. “Resourceful heroism is time-consuming. Sir.”

Our company clerk, Private First Class A. Bierce, almost smiled. He sat in a corner, in the shadow of his massive manual typewriter, quietly listening, absorbing all. PFC Bierce had a poker face and a receding hairline. He had a hint of south of the border in him, like Fernando Lamas.

He had a semi-famous name, too, although he didn’t know that I or anybody in the United States Army knew. Bierce worked l

ong hours at the keyboard, but I never saw his work. To a man, we left him alone. Veteran soldiers knew that you did not make an enemy of a company clerk.

Captain Papersmith raised a delicate hand. He had a pencil neck and pale, translucent skin you could see veins through. He was not young, thirty-five years of age at the very minimum. His background was as classified as our duty station, the 803rd Liaison Detachment.

He said, “Indeed you were resourceful, but cease the sarcasm, Private Joe. I do believe that the air conditioner requisition indicates you’re ready to assume more responsibility.”

“Yes sir,” I said warily. In the army, “more responsibility” translated into a dirty detail.

Ziggy didn’t say anything. Ziggy didn’t speak unless spoken to and sometimes not then, unless you got him going on Mars and Mariner 4’s approach to and imminent arrival above the Red Planet. The builders of that satellite guaranteed that, once and for all, Mariner 4 would separate Martian fact from Martian legend, an assurance that tied his stomach in knots.

“Stop pouting, Private Joe. I don’t understand you men, Joe and Zbitgysz. There are two of you, replacing one. Am I overworking you? Is the supply room such a burden?”

Ziggy and I had replaced former Supply Sergeant Rubicon, who had received a compassionate reassignment to Fort Lee, New Jersey. His German war bride, widow of a Wehrmacht lieutenant killed at Stalingrad, had turned out to be the forty-something lawfully wedded wife of an SS officer who’d been stationed at Buchenwald. Simon Wiesenthal had recently thrown a net over him in Argentina.

I’d eavesdropped on Sergeant Rubicon as he’d pled ignorance to a chief warrant officer from the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) named R. Tracy.

Besides having a name from the funny pages that hung around his neck like a five-hundred-pound albatross, CWO R. Tracy bore an extremely strong likeness not to square-jawed Dick, but to Lee Harvey Oswald. The days since November, 22, 1963 must’ve been hell for him, the poor bastard the object of wary stares and the butt of endless jokes.

I’d liked Sergeant Rubicon and believed him even if CWO Tracy hadn’t. He was especially devoted to his stepdaughter, who’d been a preschooler during World War Two. She’d had vivid memories of “airplane skies,” which was her term for B-17 raids, hundreds of the bombers visiting at a time. Rubicon had hoped she’d someday get over her nightmares. I did too.

When Rubicon had said his piece, CWO Tracy had looked up from his notes with an Oswaldian smirk, saying nothing. Yeah, Rubicon had gotten a ticket home, but then what for him? The next day, the 803rd was without a supply sergeant.

“Is it a burden, Private Joe?” the captain pursued.

I gave the one acceptable answer. “No, sir. Not a burden.”

“You will also assist PFC Bierce with clerical duties as I see fit. Bierce works like a dog.”

Our official MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) was Duty Soldier, so “more responsibility” of any ilk could be piled on us. In effect, we were coolies. But Ziggy and I as clerks? That was a crock of guano. The captain was laying a trap.

I looked at PFC Bierce. Pretending to ignore us, he carefully scrolled more paper into his typewriter. The incommunicative Bierce was a mystery man in many respects, materializing at the 803rd from parts unknown.

He had replaced Specialist-4 Cleon, who’d been surprised in the latrine by our super-patriotic executive officer, Colonel Jake Lanyard. A transistor radio to his ear, SP4 Cleon had been masturbating to Hanoi Hannah, North Vietnam’s equivalent of Axis Sally and Tokyo Rose.

I’d listened to her, too, to her Hi, GI Joe. How are you? It seems to me that you are poorly informed about the going of the war, to say nothing of a truthful explanation of your presence here to die or be maimed for life. She didn’t sound particularly sexy to me. My image of Hanoi Hannah was closer to Ho Chi Minh than Jayne Mansfield. But to each his own.

Colonel Lanyard did not drink, smoke or chew. I knew zilch of his love life, here or stateside, but I doubt that he consorted with women who did drink, smoke or chew. Ultra-clean living lent a high level of self-righteous intolerance to the colonel. His only known vice was that he had no known vices.

General Whipple had overheard the enraged Colonel Lanyard bellowing at Cleon, calling him, among other things, a degenerate and a commie punk. His intervention had prevented Lanyard from blowing PFC Cleon’s head off with the .45 that was on his hip day and night. The colonel did manage to get Cleon convicted of misdemeanor treason or some such and sent to Leavenworth to pound rocks.

I wasn’t sure where Captain Papersmith came from either and what he did here at the 803rd besides bossing us around. He called himself the company commander and detachment adjutant. His primary duty seemed to be reviewing paperwork and sending it up and down the line.

Which brings me to our 803rd Liaison Detachment in general. My dictionary defined “liaison” as communication between different groups or units of an organization. To “liaise” was to effect or establish a liaison. A “detachment” was a small unit, created for special duties.

I was unable to detect any duties, special or otherwise, in the Fighting 803rd, nor any communication or useful activity whatsoever. And what of the previous 802 liaison detachments? Had the original crossed the Delaware? Had one established liaisons at Antietam and Belleau Wood? I’d researched the unit’s history and found no history, let alone any active “liaison detachment,” should there ever have been such an animal.

Anyway, why were we commanded by a brigadier general and a bird colonel when we were few, doing little?

The 803rd’s Annex across the street was the key. Had to be.

Our personnel jackets were on Captain Papersmith’s desk. He knew exactly what he had in us. I was a draftee who’d get out the same way as I came in--as a slick-sleeved private. There was a drinking-on-duty incident and an altercation with a sergeant. My military downfall was my temper and my big mouth. In the army, insubordination was worse than being an atomic spy.

My parents summed me up pretty well as a misfit with alcoholic tendencies who didn’t want to be anything when he grew up, should that miracle occur. I was a college boy, a professional student. In the space of six and a half years, I’d earned fewer than two years of college credits in any specific discipline. I changed majors like I changed underwear. The Selective Service System had finally lost patience with my academic buffet and invited me to take my draft physical.

I was the diametric opposite of my brother, Jack, who had flown through undergrad work and was a doctoral candidate in aerodynamics and fluid mechanics. I suffered mightily in comparison. In addition, my mother and stepfather taught mathematics and English, respectively, at a junior college. My family had the three Rs covered. To call me a black sheep was to insult the species.

It’s sad that I can’t return from The Great Beyond to counsel myself. I sure as hell could’ve used my wisdom.

Ziggy had more than his share of problems, too. He was a high school dropout and an enlistee who’d been on the ragged edge of a Section Eight from the day he’d raised his right hand. He’d been promoted to PFC and demoted to private more times than Carter had pills. He should’ve had zippers on his sleeves.

Ziggy had been hauled before a judge for some offense or another. The judge had let him pick between the jailhouse and the recruiting station. It was routinely done in those days. In 1965, there was more of that flavor of patriotic zeal filling the ranks than the Pentagon cared to admit.

Ziggy and I had one thing in common. Nobody wanted us. My original MOS was cook. Ziggy was an ammo loader. The army had sent me to cook’s school, where we prepared pots of greasy stews that reminded me of witchcraft and cauldrons. They’d taught us to cook spaghetti that was crisp and bacon that was not. Ziggy had no formal education in ammo loading.

Neither of us had found our assignments vocationally appealing. This must have showed. They had us pegged as jack-offs who could get you killed, either poisoned or blown to smithereens bef

ore Victor Charles had an opportunity to take a lick. We’d bounced from here to there, winding up at this puzzling organization, most likely at random.

As the 803rd’s duty soldiers, we cleaned the latrine and mopped floors. In our supply room duties, we humped tons of mimeograph paper and file folders and carbon paper and adding machine tape and punch cards and correspondence to the door of the mysterious Annex. The punch cards arrived in bricklike packages. If they’d been actual bricks, we’d handled enough of them to build a medieval cathedral, flying buttresses and all.

“If you typed, I could assign you duties less menial,” the captain went on.

I could hunt and peck, but Ziggy didn’t know which side of a Remington was up. Biting the hook, I quickly lied, “We do know how to type, sir. Fifty words a minute, though we’re a little rusty.”

“I wasn’t aware,” the captain said.

Ziggy piped up, “Sir, I don’t know how to type.”

I gave Ziggy an elbow. You never knew when that prodigious brain would jump out of gear.

The only instance in which you ever ever ever volunteered in this man’s army is if they asked if you typed. Typists were scarce, and if you said you could, truthfully or not, they invariably sat you in front of a typewriter in a warm, dry place.

Volunteering for anything else, forget it. I’d learned that the hard way in a morning formation during basic training at Fort Ord, California when a sergeant with a clipboard had asked if anyone had a driver’s license. Several suckers, me included, thinking ahead to an easy day behind the wheel, had raised our hands and spent the rest of that easy day driving a push lawnmower on the parade grounds.

“As you were, Zbitgysz,” Captain Papersmith said. “I say you’re typists, you’re typists. They’re Specialist-4 E-4 slots, men. The sky’s the limit if you behave and apply yourselves.”

Dragon Lady

Dragon Lady